I wanted to write about silences and terror and acts that hover over generations, over centuries.

- Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes, (2023, 26)

Imagine an ignorance militant, aggressive, not to be intimidated, an ignorance that is active, dynamic, that refuses to go quietly—not at all confined to the illiterate and uneducated but propagated at the highest levels of the land, indeed presenting itself unblushingly as knowledge.

- Charles W. Mills, ‘White Ignorance’ (2007, 13)

In The Pregnancy ≠ Childbearing Project: A Phenomenology of Miscarriage (2017), I argued the need to ‘disentangle the plot’1 of pregnancy as it is uncritically tied with productive motherhood and childbearing, and as it has a naturalised and uncritical access to heteronormative gender privilege. With the premise that ‘whiteness is property,’ as argued by Cheryl Harris in 1993, in this paper, I link the ways in which pregnant embodiment, validated in the context of whiteness as only for the sake of bearing a child, as a ‘success’ story for the white entitled few, is also an entitlement of whiteness built on a trauma history. With this entanglement shaped around white ignorance and whiteness as property, along with the legacy of intergenerational trauma and the history of slavery, birth narratives are uncritically framed and reframed around a selective understanding of the birth experience.

With focus on the U.S. context, I will be extending the work published in my graphic novel and philosophical analysis of pregnancy and miscarriage by explaining how the history of birth privilege is a history of white privilege. As backbone to this kind of inquiry, I also offer an analysis of two documentary narratives about the high maternal mortality rates for women of colour (and black women in particular), highlighting stories around the preventable deaths of black women: Aftershock (2022) and Nekeshia Wall’s Reclaiming Power: The Black Maternal Crisis (2021). Much of this critique was informed by conversations with my named contributor, Valencia Andrews,2 a New York–based doula, who provided insight into the birthing experiences of BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of colour) women, particularly in the New York and greater tri-state area.3

Utilizing the current scholarship in Critical Trauma Studies, along with reframed historical narratives about the legacy of slavery as it informs current social and cultural practices and mythologies, I draw selectively from the scholarship of Joy DeGruy, especially her work, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome (2005), borrowing some of the methodology of Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (2007); Myisha Cherry’s idea of Lordean, antiracist rage from The Case for Rage (2021) as informed by Charles Mills’ work on White Ignorance. Noteworthy to my claim here is also the ethnographic work of Khiara Bridges in Reproducing Race (2011).

Narrative autonomy in relation to one’s own pregnancy and birth can easily erode in the wake of miscarriage and pregnancy loss, in the situation of giving birth already framed in the context of whiteness and white privilege, and in the selective and sometimes deceptively romantic stories about postpartum recovery and the naturalised ‘selflessness’ of motherhood. One is already ‘framed’ when all comportment is meaningful only when it is ‘for the sake of the/a baby.’4 Therefore, a reclaiming of narrative autonomy must begin by establishing the right to exercise and to challenge or to even refuse procedures that lead to a greater health and trauma risk, which often manifests in the medicalised assessments and recommendations during pregnancy and birth through to postpartum; this is disparately accessed and experienced for women of colour in particular.5

Full narrative autonomy is reserved for the privileged few, maintaining a productive whiteness, with successful and ‘efficient’ childbearing to protect and validate the entitled few against the many who cannot and will not conform to this dominant narrative. For many who cannot conform to this narrative, the experience of pregnancy, and/or the experience of birth, as well as the experience of post-partum (in which one does not get to return to one’s former self), loses its open, existential phenomenality. This white privilege has parallels to fertility privilege6 in which perceptions of biological parenting has become tied to the making and preserving of the normative cultural phantasms of white supremacy and American exceptionalism, coded in assumed protections over the idea of the ‘nuclear family’ that exemplify American ‘family values.’

I hope to demonstrate –at least tentatively– the operating thread that entangles white privilege with who gets to give birth, who has power over when and how they give birth, and who gets to survive their birth experiences. Then, the hope is to reveal this thread in order to break it (see Figure 1). I also challenge the co-opting of childbirth narratives as a natural ‘right’ or as if part of a ‘natural order,’ so that there can be a reclaiming of the trauma survivorship latent to and erased by these dominant cultural perceptions. This is the question I am compelled to ask: How best to reclaim the pervasive loss of narrative control over when and how to ‘give birth’ and to interrupt dominant narratives over the phenomenon of giving birth, especially when it comes to ‘who’ and ‘how so’?

For Valencia Andrews, as an experienced birth doula, these questions are most relevant to break with the framing and subsequent disruption of the systems of white supremacy as they consolidate the available narratives about ‘who is deserving’ of humanization and who remains in service to humanity, who has access to rights and entitlements, and who must first ‘earn’ access. Even with access to medical supports and infrastructure to the birth experience, the dominance of white privileges and entitlements has not changed in any substantial way; rather, according to her observations and professional experience, white supremacy has only expanded in its opportunities for commodification and profiteering with regard to birth privileges. On this point, she commented that there is a systematic

[…] challenging [of] autonomous decision making throughout all stages of pregnancy and postpartum, medical staff calling Child Protective Services (a thriving business where Black children are still, in a way, being ‘sold’) on new BIPOC mothers for exercising actual rights like: vaccine refusal (specifically the Hepatitis B shot), self-discharge ‘Against Medical Advice’ (AMA) when feeling unsafe or for any reason, refusing other hospital based policies that are posed as law, or pushing formula to BIPOC communities already generationally traumatized around breastfeeding. It’s so sinister and no mistake that they build the nursery in a separate wing or floor [so that it] discourages the body/child connection necessary to support milk production.7

Important in challenging the disconnected relation of birth experiences, narrative autonomy in birth survivorship could make these reconnections reparative against the current threaded genealogy of white supremacy with misogynoir.

I. Norms and Narratives

Narrative […] facilitates the ability to go on by opening up possibilities for the future through retelling the stories of the past. It does this not by reestablishing the illusions of coherence of the past, control over the present, and predictability of the future, but by making it possible to carry on without these illusions.

- Susan Brison, Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of the Self (2002, 104)

[R]ights in property are contingent on, intertwined with, and conflated with race. Through this entangled relationship between race and property, historical forms of domination have evolved to reproduce subordination in the present.

- Cheryl Harris, ‘Whiteness as Property’ (1993, 1714)

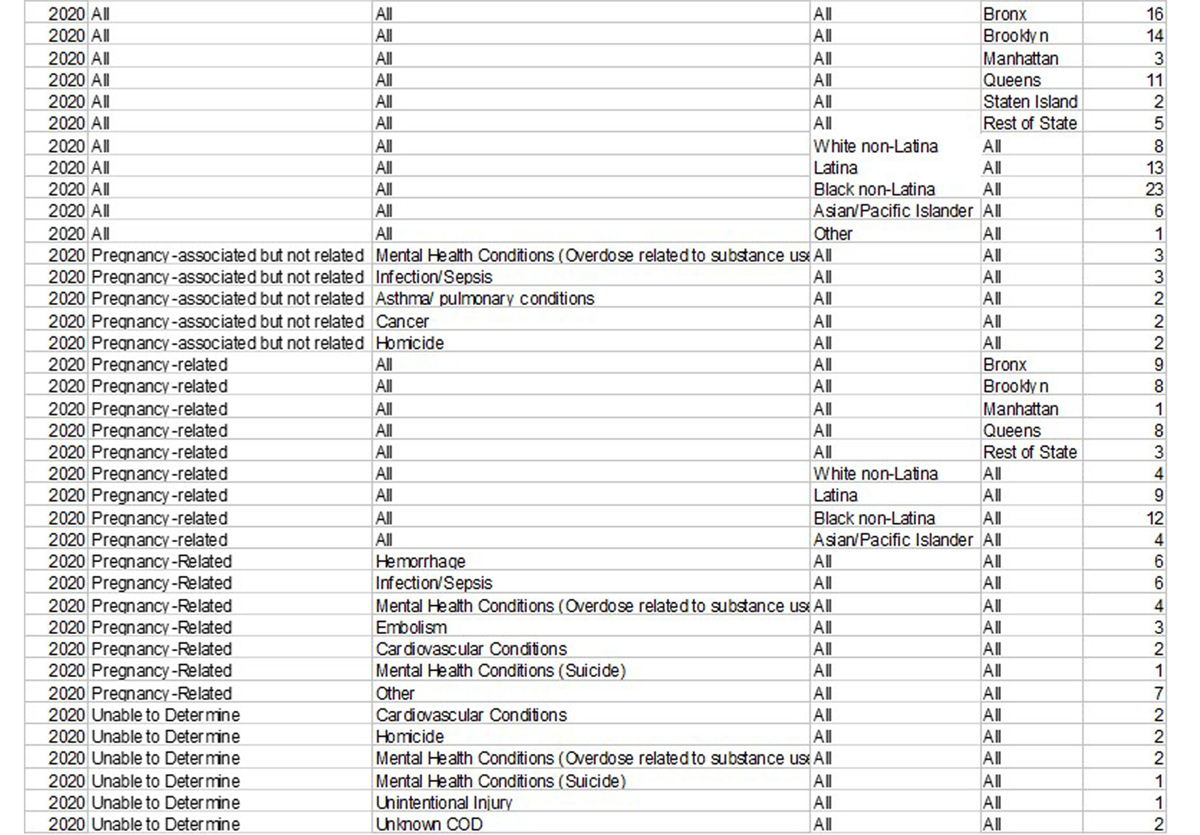

In Nekeisha Wall’s documentary, Reclaiming Power: Black Maternal Crisis (2022), in the context of New York City, there is a claim made: that to be ‘black and birthing’ is to incur a high-risk pregnancy twelve times the average. I found mixed reports (and even questionable modes of reporting) on this statistic (See Figure 2),8 but Black women are four times more likely than ‘their white counterparts’ to die in or right after childbirth.9 Andrews confirmed my suspicion about the issue of reporting in our conversation: ‘I can no longer count how many times I’ve been a witness to this show of force and dominance.’

Screenshot of the downloadable spreadsheet labelled, ‘Copy of Maternal Mortality Data Dictionary v6.xlsx.’ The columns indicate from left to right: Year, ‘Related’ [no other indication of category], Underlying Cause, Race/ethnicity, Borough, and [Number of] Deaths. From the NYC Open Data site on Pregnancy-Associated Mortality (accessed October 2024): https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Health/Pregnancy-Associated-Mortality/27x4-cbi6/about_data.

As a starting point, I want to imagine that the phenomenon of giving birth was accompanied by all of the rights and freedoms that could be afforded to the one who gives birth, and the experience carried with it all of the power and resources one needs for self-determination in the circumstances surrounding pregnancy and birth. Specific to this analysis, I want to also imagine that this self-determination included a freedom of expression, engagement, and most importantly a resistance and refusal of the ordinary tropes and dominant narratives of pregnancy (i.e., birth and the postpartum state). So many of these ordinary tropes and dominant narratives are underwritten by white heteronormative expectations and values. These ‘white-washed’ tropes therefore conceal and naturalise white heteronormative values within assumptions about what can be expected when it comes to becoming pregnant through to giving birth with all its postpartum entailments.

This (imagined) narrative autonomy could then also include a fundamental political pluralism, giving permission for the strong yet often conflicted desires over pregnant embodiment and its assumed outcomes and expectations, all while fundamentally protecting one’s bodily autonomy. One’s narrative autonomy could be supported and maintained throughout the process leading up to the event of giving birth, given to a post-partum state with self-directedness independent of the ‘productiveness’ of that pregnancy. This narrative autonomy would guide decision-making and planning, setting a tone for what is possible and protected in the birthing theatre, what supports and interventions are available and provided, and how risk of threat of harm or death is managed, minimizing any traumatic impact on the birthing person as they might ‘carry to term.’ This narrative autonomy ought to also be underwritten by an assumed power of self-determination as to whether or not to give birth at all.

Yet, as Myisha Cherry puts it, following Audre Lorde’s insights, ‘People of color were never meant to survive in a world of white supremacy’ (2021, 168). This is evidenced in the documentary Aftershock, in which Shamony Makeba Gibson, a young Black woman who died prematurely postpartum, is profiled (See Figure 3). Her mother, Shawnee Benton Gibson, describes how the maternal mortality rate ought to be considered as any other ‘epidemic’:

I never thought that this would happen to my family because I do reproductive justice work […] but you know, just also, why wouldn’t it? […] We’re black and brown, and […] she’s a woman. She was having a baby, so why would we think we would be exempt? Because we have the knowledge? Knowledge doesn’t save you from this epidemic. (Aftershock, 21m5s–23s)10

LEFT: Shamony Makeba Gibson, pregnant and holding her daughter, Anari Naja Maynard. Shamony was one of the women profiled in the documentary, Aftershock. Image reproduced with permission of the Family of Shamony. RIGHT: Amber Rose Issac, the other woman profiled in the documentary film, Aftershock, who also died post-childbirth. In both cases, their deaths were preventable. Image reproduced with permission from the family of Amber Rose Isaac.

Currently, in the wake of the recent Dobbs decision in the U.S.,11 there is manifest erasure of narrative control as well as the control over one’s power and agency to reproduce. Without federal protection for reproductive care, there is an unbridled privileging of whiteness with socio-political platform, through policy and white nationalist ideology, a continued supplying of economic and social resources to whiteness through property, also seeped in white ignorance.12 As Michelle Goodwin states, writing for the ACLU:

[The] racist origins of the anti-abortion movement in the United States […] date back to the ideologies of slavery. Just like slavery, anti-abortion efforts are rooted in white supremacy, the exploitation of Black women, and placing women’s bodies in service to men. Just like slavery, maximizing wealth and consolidating power motivated the anti-abortion enterprise.13

This platforming of anti-abortion conservativism grants unearned credibility to women who benefit from a naturalised whiteness, a naturalisation rooted in the colonial interests of white women, in capitalizing on their labour, and their potential to contribute to the population as white.

Jennifer Morgan, in Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic (2021), accounts for this capitalization on labour (147–148), and then notes the way historians account for the Middle Passage and the early slave trade but neglecting the mechanism naturalising white interests:

Historians’ perspective […] is rooted in nineteenth century formulations of the distinction between public and private realms, a distinction already deeply marked by the claims of whiteness and civility when it emerged […]

The machine of the early transatlantic slave trade did not simply feed on family [… but] was sustained by creating a fiction in which the meaning of kinship was subsumed by racial hierarchy, the very thing that rendered familial ties dispensable in the eyes of slave traders. (150)

Morgan makes it clear that when it came to the ‘importance of reproduction,’ the calculations in the context of slavery meant that pregnancy and birth were understood only through commodification, such that ‘Neither femininity nor maternity offered protection from commodification’ (182). Andrews, in our conversation, also argued that this was

[…] evident to me, as a birth worker, who takes into consideration how my clients can and/or should be supported in accessing or reclaiming their femininity and maternity during the postpartum period – something I feel many are robbed of with unnecessary C-sections leading to unnecessary stress and ultimately, (or early) death. [And, for example, the] rushed labour and delivery for the mom who’s going home to a 5th floor walk-up in NYC housing only serves the system.14

Further fuelling my inquiry is the question of how I might best connect the legacy of slavery, unaddressed and in its complex trauma history (especially in the U.S. context), is how it is actively informing current testimonial injustices.15 The pervasive misogynoir in reproductive politics, and – frankly – the enragingly16 high maternal mortality rates for women of colour (especially black women), actively constricts, regulates, and destroys the power and autonomy over one’s birth narratives and birth stories (See Figures 3&4).

Khiara Bridges, in Reproducing Race, identifies an equivalence of ‘American-ness with economic self- sufficiency’ not only through history but also through policy. There is a further equivalence, what she calls a historically ‘axiomatic relationship’ of ‘American-ness with whiteness’ (2011, 218–220): ‘Indeed, “American-ness” had more to do with race than with citizenship.’ This undermines even the birth right status of African Americans in a way that, in contrast to more recent European immigrant generations (as in the case of Italian and Italian-Americans, for example), who, through whiteness and with an acceptance of capitalist values, the proximity to whiteness by default offers then a direct and expedited access to citizenship entitlements regardless of immigration status.

Although it is in reference to the case of her grandmother’s attempts at passing as white, Cheryl Harris, similarly states in ‘Whiteness as Property’ that:

Becoming white meant gaining access to a whole set of public and private privileges that materially and permanently guaranteed basic subsistence needs and, therefore, survival. Becoming white increased the possibility of controlling critical aspects of one’s life rather than being the object of others’ domination. My grandmother’s story illustrates the valorization of whiteness as treasured property in a society structured on racial caste. […]

Whites have come to expect and rely on these benefits, and over time these expectations have been affirmed, legitimated, and protected by the law [and …] American law has recognized a property interest in whiteness. (1993, 1713)

Whiteness as property – an operation I want to use to add charge to my critique – is concomitant with white ignorance as Charles Mills has also described it, and this is a springboard for my use of Myisha Cherry’s The Case for Rage. Cherry cites Mills’ white ignorance as a ‘convenient amnesia about the past,’ coupled then with white scepticism, which is ‘a hostility to and resistance of testimonies to racial injustice,’ (2021, 43–44). With both white ignorance and white scepticism actively engaged in the cultural imaginary, there is an uninterrupted, illusory neutrality to policy around reproductive health and access to resources.17 Arguably, then, when there is resistance to current surveillance and controlling policies over reproduction – in particular, those that underwrite the norms and overwrite the latent narratives of who gives birth and how (or if) they can do it – it remains in the register of white privilege.

Cherry outlines another dimension to the violence of whiteness, as the white empathy that emerges when the motives, tone, or freedoms of action for white people are presumed to be given a benefit of the doubt, ‘when all else is not equal’ (44–45). Cherry then names the ‘the triple emotional burden of oppression … when members of racially oppressed groups experience injustice, carry the anger in response to it, and then work hard to convince others that they have a right to be angry.’ No matter the degree of acknowledgment of the injustices and cruelties of the past, including slavery, all the same, ‘racism is at work.’ When it comes to present testimonial injustices surrounding U.S. reproductive politics, we might restate it as Cherry argues, ‘white ignorance, skepticism, and empathy remain’ (emphasis added, 47).

In The Pregnancy ≠ Childbearing Project, I characterized my first experience with pregnancy18 as an embodiment of a ‘cis-white-het dream,’ (2017, 1), full of naiveté that could easily be re-read in the context of white ignorance. More recently, I have argued19 that there is a material and cultural prioritisation of white (women’s) psychological and subjective experience of trauma against all other experiences and positionalities in relation to intergenerational trauma and systemic, racialized trauma exposure. The political accountability for the lack of failsafe mechanisms against these latter forms of trauma have yet to yield the transformative power that Cherry argues for in her defence of Lordean rage. In short, here, too, is what she calls the evidence ‘of racism and also evidence of social trends that deny, downplay, and prevent uptake. The triple burden continues’ (47). These are the same elements that have led to the epistemic injustices and disproportionate maternal mortality rates that carry an even deeper affective force as there is a further conditioning of future and extension of intergenerational racialised traumas.

Susan Brison, in Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of the Self (2019), describes how, after first being ready to conceive and experience possible childbirth, having developed the ‘very non-universal’ desire to have a child, she was violently sexually assaulted (43–44).

In order to construct self-narratives, we need not only the words with which to tell our stories, but also an audience able and willing to hear us and to understand our words as we intend them. This aspect of remaking the self in the aftermath of trauma highlights the dependency of the self on others and helps to explain why it is so difficult for survivors to recover when others are unwilling to listen to what they endured. (51)

For Neel Shah, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the Harvard School of Medicine, ‘every injustice in our society shows up in maternal health and in maternal health outcomes’ (Aftershock, 28m33s). While it is important to show evidence of the ways in which birth has normative and narrative value for the cultural imaginary dominated by white privilege, there is, too, the meaner20 operation of white privilege in medicine proper, especially as it is given to the medicalisation of pregnancy and birth. Although I am not fully subscribed to the idea that medicine could be reflectively accountable for these injustices, Shah explains how journalists told the stories of maternal deaths, which led to the government to begin to track maternal mortality rates and its differentials more systematically starting in 2018 (Aftershock, 28m48s).

There are also trauma-inducing disparities at the site of post-partum, both gendered and racialized. This is in the context of a history of ‘medical apartheid’ as Harriet Washington (2006) narrates it – from forced sterilization to genocidal distribution of birth control – marking a notable fissure in the ways in which what is ‘known’ or ‘not known’ by medical science reproduces that history of violent experimentation and oppression. There are many ways in which there are grievable losses in narrative and epistemic authority over the ‘how’ and ‘who’ of birth, complicated by the denials and discrediting of the pregnant subject as the central subject of and a most vulnerable stakeholder in the situation.

It is worth noting that although my focus here is on a particular kind of operation of white privilege, whiteness operates analogously in other norms and narratives of medicalized care. For example:

In health care delivered to Indigenous people, acknowledging and reflecting on the privileged position of the dominant racial and cultural group is integral to understanding racism and how it is constructed and practiced; so it does not remain unconscious. […] In a healthcare setting, the focus is usually on Indigenous disadvantage rather than the impact of Whiteness and its associated privileges. (Durey, 197)

So, a position I am subscribing to here is that ‘One of the reasons why we see such a high rate of black women and women of African descent dying while they are laboring, dying post-partum is racism […] white supremacy [and] structural racism.’ (Reclaiming Power, 4m35s–5m02s). As the relationship between medicine and the pregnant body has been one of mistrust and de-humanization, especially for those who do not meet the norms and narratives of the ‘cis-white-het dream’, there is still much to learn about the affective transfer of the history of slavery and anti-black racism as a trauma history.

II. ‘The Soul Killing Effect of Slavery.’

If they had just listened to her during that postpartum time.21

- Shawnee Benton Gibson, mother of Shamony Gibson, from the documentary Aftershock (2022, 9m30s)

A complaint can be how you learn about institutional violence, the violence of how institutions reproduce themselves, the violence of how institutions respond to violence.

- Sara Ahmed, Complaint! (2021, 180)

Jennifer Morgan, in Reckoning with Slavery (2021), raises an important question for my analysis as it also is rooted in a recovery narrative. She describes the conditions of what is today New York City but at the end of the Dutch period (1613–1664), in which there was a growing population of enslaved Africans and West Indians experiencing ‘exceptionally high infant mortality rates.’ She then asks that, if

many infants succumbed to serious illness before the age of two[, then:] What manner of strange grief must have settled on women who were accustomed to raising children among other women but who encountered one another only infrequently in the crowded and filthy streets of lower Manhattan without the children who would normally have occupied the female spaces of their past? (emphasis added, 240)

This question threads the needle in describing a place of incredible and violent epistemic loss. In this context, the social and political infrastructure was vicious and there was nothing available to build a language and narrative imaginary around postpartum experience and survivorship. This meant only erasure against the intergenerational traumas of slavery, systemic oppression, and pervasive misogynoir. Whatever social or intergenerational knowledge that could be formulated, instead was replaced with alienation and a racialized, socioeconomic institutionalisation of ‘testimonial quieting.’22

Morgan goes on to also tell a story about a woman whose ‘child was dead inside of her,’ dying of the condition while still on the slave ship, the James in 1675, noting that, “all the other women on board must have viscerally felt the link between her pregnancy and death” (245). If we follow what Joy DeGruy suggests in Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome (2005), that, with the history of enslavement, ‘viewed through the historical lens of slavery and its aftermath,’ then we can begin to understand how trauma can transfer, having ‘roots in slavery’ and then be ‘passed down through generations.’23 DeGruy suggests that

if a trauma is severe enough, it can distort our attitudes and beliefs, [… and] this pattern is magnified exponentially when a person repeatedly experiences severe trauma, […] it is much worse when the traumas are caused by human beings. (8–10)24

In this part, I borrow very much from the work of Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection (2022) as a style of analysis so that I can access the relationship between white supremacy and performativity. As a shorthand, my thinking is that when white bodies give birth to white babies, there is a kind of ‘authenticity’ in performance that no longer translates as a kind of performance. As Hartman argues in the updated preface, ‘The Hold of Slavery’:

Temporal entanglement best articulates the still open question of abolition and the long- awaited but not yet actualized freedom declared over a century and a half ago. […] Conservative scholarship had minimized the role of racial slavery in the making of capitalist modernity, failed to theorize race, characterized slavery as a premodern mode of production, denied the magnitude of the violence required to produce the human commodity and reproduce the relations […]. (xxix, xxxvi)

There is no disconnect or dissonance between the role of corporeal phenomena and the expectations and outcomes with those dominant scripts, norms, and narratives described in part one. In whiteness, one can become the part that they play with a kind of freedom from invisible labour and the burdensomeness of a double consciousness.25 Through the birth experience, access to white privilege allows for a suspension of perceived risk and threat that can come with unaccounted for and disproportionately distributed trauma knowledge, even the intergenerational kind. To those who do not ‘authentically’ resemble the performance of white entitlements, of a willing ‘mother-to-be,’ or maintain the normative and white-washed (also ableist26) position of the compliant woman ‘without complaint,’ these dominant scripts effect a violent and surreptitious suspicion that can excite surveillance and coercion for the sake of the interests that guard ‘whiteness as property.’27 As Harris describes it, the ‘persistence of whiteness as property [is in] the legal legitimation of expectations of power and control that enshrine the status quo as a neutral baseline, while masking the maintenance of white privilege and domination’ (1993, 1715).28

Similar to Hartman’s approach, Cherry uses DuBois’ essay, ‘The Souls of White Folk,’ to think about how ‘whiteness’ had emerged as a kind of ‘wonderfulness,’ a new religion of ‘whiteness as social identity’ (2021, 98–99):

This wonderfulness, they believed, […] granted them certain entitlements, manifested in imperialistic projects, according to DuBois. He refers to this as the “right to ownership of the earth, forever and ever, Amen!” Ownership was not only of the land and sea. Whiteness made white people feel entitled to the bodies that dwelt there. To remember whiteness and keep it holy, then, is a racial rule that tells us that we should recognize and remember the glory in and of whiteness – for this glory is a trait that is exclusive to whiteness and lacking in other people.

With a kind of ‘enragement,’29 this is the thread – as a kind of connective tissue – from whiteness to those corresponding privileges that needs interruption and urgent intervention, if not also a severance from the operations of naturalized whiteness. This is Hartman’s approach:

This intervention is an attempt to recast the past guided by the conundrums and compulsions of our contemporary crisis: the hope for social transformation in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, the quixotic search for a subject capable of world-historical action, and the despair induced by the lack of one. […]

[The] failures of reconstruction still haunt us. (18)

And, for Hartman, ‘The exercise of power is inseparable from its display’ (9).

Bridges supports this in her analysis of ‘deservingness’ and its ‘moral economy’ as it currently operates as a form of performativity in defence of whiteness (214–215). In analysing the emergence of the racialized category of ‘welfare queen,’ Bridges discovered how ‘the moral economy of deservingness has… its own history,’ in which the ‘deserving poor’ are ‘capable of receiving pity, benevolence and compassion,’ but the ‘undeserving poor,’ ‘produced these (ungodly) situations themselves’ (214). Bridges adds an important analysis of how ‘deservingness’ via access to privilege and property worked alongside the perceived ‘undeservingness’ of poverty as an extension of white entitlements:

Those persons who have failed to “prosper or contribute” within the culture of capitalism, but who do so other than as a result of a conscious repudiation of the needs and requirements of capitalism, are accepted as the “deserving poor.” (216)

Although Bridges suggests that ‘the category of the undeserving poor was originally populated entirely by white people,’ (author’s emphasis, 215), in this history, this category quickly shifted in its racialisation: ‘Black people’s performance of a behavior facilitates the behavior’s alignment with undeservingness [… such] that Blackness is always already aligned with undeservingness’ (216).

It is the way in which Hartman looks at the ‘constricted humanity’ given to slavery as performance, in its contradictions, but less so as forms of ‘spectacle,’ that I think is worth adapting for my purposes here. And, in fact, the risk is that my appropriation fails in the context of my use. By analysing those ‘mundane displays of power’ (66), the forms of ‘violence enabled by the recognition of humanity, licensed by the invocation of rights’ (7), by ‘defamiliarizing the familiar,’ (2), Hartman’s analysis provides guidance for how the subject negotiates the untenable situationality of ‘the particular mechanisms of subjection’ (191) in which ‘coercion and calculation become interwoven in the narrative as in the law’ (193).30

An example of this subjection and performance is in the ‘coerced theatricality’ and ‘degrading hypervisibility’ of the slave trade (56–57), in which the enslaved person goes into the market seemingly ‘cheerful and happy.’ Implied in this is a more sinister disavowal of pain and a form of denial that Hartman imagines through the lens of white supremacy:31

No, the slave is not in pain. Pain isn’t really pain for the enslaved, because of their limited sentience, tendency to forget, short-lived attachments, and easily consolable grief. Most important, the slave is happy and, in fact, his happiness exceeds ‘our’ own. (author’s emphasis, 55)

Hartman adds a key aspect to this interrogation of the inherited, racialised dynamic of subjection and performance: By disassembling the ‘benign’ scene, we confront the everyday practice of domination in

the daily routine of terror, the nonevent, as it were. […] Are the most enduring forms of cruelty those seemingly benign? Is the perfect picture of the crime the one in which the crime goes undetected? (66)

This is, in Hartman’s words, ‘the soul killing effect of slavery’ (76).

As I argue it here, this is the thread that ties systemic anti-black racist practices, misogynoir in the birthing theatre, all the way back to a rolling, unmediated trauma history from slavery. So, I am compelled to ask: In what ways does the current narrative around birth for Black women carry this intergenerational trauma history?

In my conversation with Valencia Andrews, she notes that, in her mind, she often found herself connecting what she observed in current standard practices of gynaecology as it seemed indistinguishable from what she imagined stemmed from the history of slavery and oppression. Her experience as a birth doula often included navigating prenatal and postnatal experiences so that they do not become collateral damage in this racialized trauma history. She intuitively understood that this is a history in which, as it connected back to the context of slavery, ‘your womb meant your worth’ and women were just ‘guinea pigs.’32 For Andrews, these connotations remained operational even today as she observed them in her clients’ birthing experiences.

There is a significant amount of testimony that feeling like a guinea pig has not left the narratives around birth, but, additionally, one is made subject to more selective and strategic ‘erasures’ and ‘smothering.’33 For example, the ways in which fear gets locked into the birth plan is something that Andrews found to be the most difficult to navigate in this care service, and, as she stated quite plainly, is just exhausting. She added, ‘It sent me back to my therapist.’ As we talked about the real, life-threatening danger of vicarious trauma, she also talked about how she took conscientious care in deciding how much plain truth she gives in the working out of a birth plan but also how fear management for the client is an essential, life-affirming part of the care practice. Fundamentally, she knows not to overwhelm but be honest; and, most importantly, it is the intimacy of care and the specificity of the birth and postpartum plan that she argued can make all the difference.34

III. Lordean Rage

The repression of slavery’s unspeakable features and the shockingly benign portrait of the peculiar institution produced a national innocence, yet enhanced the degradation of the past for those still hindered by its vestiges because they became the locus of blame and the site for aberrance.

- Saidiya Hartman, (2022, 235)

So we definitely are in a black maternal crisis right now.

[…] It really boils down to bodily autonomy and agency, right? Centering that person first.

As narrated in the film Aftershock (2022), the integration of midwifery care in Europe (as opposed to the for-profit practices in the United States) has contributed to a reduction of maternal mortality rates (32m7s). In the film, there is a defence of the shared decision-making model yet, that is not the model used currently in most U.S. hospitals (32m32s). The shared decision-making model is intentionally co-constitutive to counter the potency of harm with an ‘intimacy and appropriateness’ of care.36 It is a co-constitutive form of knowledge-production in which the labour of knowing and the capacity for activating knowledge is better distributed to the pregnant person, which is important for any birth/labour/even postpartum narrative.

To the degree that there is a larger sabotage of pregnancy and birth knowledges in the language of what is considered part of a greater ‘public good,’ we can find a wrangling (or maybe a strangling?) of the discourses over one’s authority and survivability of the ‘exceptional situation’ of pregnancy. Added to this is Hartman’s characterization of the concept of the public good, ‘as it can be distorted,’:

[H]ealth, safety, public good, and comfort of citizens were predicated upon the banishment and exclusion of blacks from the public domain. If the public good was inseparable from the security and self-certainty of whiteness, then segregation was the prophylactic against this feared bodily threat and intrusion. […] The integrity of the white race delineated the public good. (351)

It has been argued that as long as L&D (labour and delivery) facilities resemble a ‘Cardiac ICU,’ then the surgeons are already always in that environment, providing leverage over the narrative of care and deciding the important markers that construct this narrative, including what ‘progress,’ ‘health,’ and ‘safety’ mean, and determining ‘what is best’ for ‘mom and baby.’ Both in conversation with Andrews and in the narratives of both films discussed here, was the often unplanned and even non-consensual ‘cutting of women,’ regardless of the birth plan. As one nurse states it in Aftershock:

The clinic population by and large tend to be Black and brown women who have Medicaid and are treated by resident learners. Every woman is getting her vagina cut open. A woman doesn’t need it, but you cut it because you need to learn how to sew. I’m at a place that is literally practising on people. (40m16s–37s)

This ‘cutting of women,’ whether it be episiotomies or the pressure to have c-sections, meant that, for Black women in particular, the exposure to a surgeon’s scalpel in the context of giving birth has a fundamentally different narrative and existential character because of white privilege.

The rate by which women of colour get c-sections and the corresponding success rate of those surgeries remain woefully disparate along racialized differences. For many women, even the fact that Serena Williams37 experienced this kind of pregnancy risk resonated because it implied a warning that the threat of not surviving one’s pregnancy is not minimized by fame or wealth. Any reduction of risk still requires that one have resources like privatized care, available in predominantly white communities, in which ‘they are on call for you’ and that any care outside of a medicalized context can only be afforded ‘out of pocket.’38

If we accept that ‘The history of gynaecology itself rests on experimentation and exploitation,’ then, in effect and in general, management strategies can fail women,39 but women of colour specifically and the BIPOC community generally. Yet, in the context of medicalised management, there remains a protecting of whiteness from harm and minimizing its risks, including those institutions in the name of and for the sake of protecting whiteness in its proprietorship.40 Hartman reads the codification of race into law, because ‘whiteness’ was ‘the most valuable sort of property,’ and ‘Blackness became the primary badge of slavery because of the burdens, disabilities, and assumptions of servitude abidingly associated with this racial scripting of the body’ (343). The inequities that frame non-whiteness, evidenced by current maternal mortality rates, remains a constant threat of violence to women of colour, without any people or particular persons intending a direct target. This violence and constant threat can – at least as I argue it here – be threaded back to this segregation history with its racialized geography. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore explains in Abolition Geography,

Racial capitalism’s extensive and intensive animating force, its contradictory consciousness, its means to turn objects and desires into money, [… its] imperative requires all kinds of scheming, […] to build and dismantle and refigure states, moving capacity into and out of the public realm. (2022, 473)

There remains today a racialised gatekeeping in the hospital model and the management style regarding the delivery of care. When it comes to the known odds of a successful vaginal birth, according to the narrative of Aftershock (2022), Neel Shah, as the doctor that leads the advocacy group, ‘TEAM Birth,’ (32m34s–37m54s), describes how race is ‘conflated with racism.’ He cites the way that, according to the current algorithms, the probability of a successful pregnancy drops from an 82.22% success rate for white women to 70.27% for African American women, stating, ‘if they are Black, they’re odds drop’ (30m33s). Shah then describes the innovations in communication he develops with community partners, training L&D doctors and nurses in ‘structured communication’ with reorganised tools like a patient-centred whiteboard (47m54s–48m51s).41

In the film, the midwives and birth workers have named the hospital model of care the ‘medical-technocratic-patriarchal model’(36m46s), a model in which doctors are trained in care ‘management’ and the management of labour. This management model rests on a history of medical experimentation and the white privileging of this knowledge as the framework for who creates this knowledge, whose interests drive this research, and who engages in the distribution of care as it is a privileged system.

The training and infrastructure of L&D, especially in the context of hospital care (as opposed to a birthing centre) creates the most disproportionate risks from birth to postpartum. The neglect is already in the support systems meant to be survivable and, as Andrews and I ended up describing it in our conversation, it is, instead, a rot from within.

At one point in our conversation, Andrews kind of laughed as she mentioned that, ‘In hospital, they can charge $75 for skin-to-skin contact time,’ but I knew her reaction to this was more out of what Cherry meant by Lordean rage.42

My thoughts here [are] not that women (including white women) are hated across the board, but that with regard to reproduction, pregnancy, birth and PP [postpartum], they – white women – too are not protected from the REALITY of the WHITE patriarchal system and the way it is built to fully support capitalism. They just have it presented to them on a silver platter, better support, SAFE bedside manner and a huge reduction in harm and medical bias as compared to their Black counterparts and that DOES make a difference in how they move forward in this world as patients/birthers/mothers/women.

In many ways, while slavery had it so that ‘Midwives [were some of the] most valued enslaved persons’ (Aftershock, 59m42s), today, the value of midwifery and doula care is negligible in the context of medicalized managed care.43 Historically, midwives had assisted in fertility care, collectively sharing the power over how to have or not have children, even if the strategies worked subversively against the surveillance and regulation of pregnancy, birth, and the bearing of children.44 As Helena Grant, a nurse and midwife, states it: ‘Midwifery care supports Black women because when it is done well, it’s anti-traumatic care’ (emphasis added, 62m12s).

So, while an intimacy of care can be the most basic yet crucial aspects to reclaiming birth equity, as stated in Aftershock, currently ‘87% of all midwives certified in the United States of America are white’ (61m40s). Andrews describes this as well with deep frustration and then hypothesises how there comes to be a devaluation of doula care in a hospital setting:45

I’ll tell you one of the hardest things is to […] spend so many months working with the family, building out their birth plan. […] And they get into the hospital room, all of that goes out the window. Even if it doesn’t seem like the situation has forced that. It’s just a matter of like saying, ‘No, I don’t want you to break my waters’ […]

I fully understand what that can do, right? And [with a hospital birth] sometimes I go to the bathroom, and I come back and I’m like, what the hell? We just talked about it. We just talked about this and now you’re going for a C-section? Like, we just talked about not doing this.

I don’t know where all of that leads us to. Where does all of this lead us to? I don’t want to say ‘hates,’ but yes, I think it is. I think hate is the appropriate word. There is a general hate for women. I’ll say that. And white women experience it too, [but also] they’re not subjected to all [of this] in some ways.46

The medicalization of childbirth and labour prioritizes birth and labour as the ‘event’ of childbearing, pre-empting the narrative autonomy of the one pregnant and giving birth. The contextual situatedness of birth becomes alienating and ripe with testimonial silencing and smothering, in which much harm and unnecessary trauma exposure exists for the subject that bears the pregnancy. This is a throughline of violent misogynoir threaded through from conception to postpartum.

Whatever self-direction or narrative autonomy over birth has been developed in this current sociopolitical context, it still has been negotiated primarily through white interests, white privilege, as well as a history of white supremacy. Any resistance to or overturning of that power of narrative as it manifests in current forms of management and oversight has been negligible but, also, in those moments of resistance, as part of the testimony and analysis offered here, gives indication of the real violence surreptitiously operating. This fits with what Hartman also asks: ‘What could a mortgaged freedom yield?’ (233), especially if being ‘emancipated without resources was no freedom at all’ (241). For Andrews, more simply stated, when discussing the need for and lack of accessible and subsidised doula care in order to survive birth in current conditions, ‘It is outrageous.’

As Sara Ahmed states in Complaint!, when it comes to institutional or system change as a response to injustice, ‘complaint’ merely tends to be dismissed and rendered ineffective, as if a misappropriation of labour, and a ‘lot of effort for little impact’ (2021, 283). Yet, most urgently, we ought not treat these testimonies as mere ‘complaint.’ In Aftershock, Shawnee Benton Gibson testifies to the New York City Council Committee on Hospitals as a grieving mother and a reproductive health care worker (34m5s–35m42s), to paraphrase her outrage: What do we do to address anti-black racism? How has it kept this epidemic going? Nubia Martin, doula and midwife assistant, at a demonstration declares: If white women were dying at the same rate black women are, it would be a national crisis! (45m57s). Healthcare provider, Helena Grant, adds to this: ‘The thing that she’s going to remember the most is what happened during her labour and birth. Every woman does. Women have to take that back’ (emphasis added, 33m30s).

Cherry, in her defence of Lordean rage, in that it is, ‘by definition, rooted in moral concern’ (52), defines it as both political and transformational (2021, 23–24 & 32):

Lordean rage is metabolized anger – […] this anger is transformative anger [… It] is morally, politically, and epistemically useful for transformative ends as it is. […] Its aim is change. […] Lordean rage is not just acceptable – it is what we need desperately. We should cultivate it, guard it, and use it in anti-racist struggle.

White supremacy prevents the humanization of those who are pregnant in their epistemic authority, in narrative complexity, and in the consideration of moral status for the victims of intergenerational racial injustice, as it is interwoven with the embodied experience of pregnancy. Even the conditions pre-pregnancy ought to be considered in this complexity, especially as Breanne Fahs suggests, what could the conditions of pregnancy and birth entail if ‘sexual violence is so pervasive’?47 With an unmitigated history of intergenerational trauma, health care is built on anti-Black racism and draws from deep reservoirs of misogyny and misogynoir.

By expanding this complexity to the conditions surrounding pregnancy in the ways white privilege preconditions birth privilege, this legacy of birth privilege carries over into current reproductive care access. Alexis Kenney in ‘A Matter of Health and Safety: Science and the State in Texas Abortion Legislation,’ analyses how informed consent practices in pregnancy, like the use of a sonogram as part of prenatal care, have been used outside of the context of care but instead as a tool to secure that a ‘woman understands the nature and consequences of abortion’ (166). This use of prenatal technology is recontextualised as if it were a part of a ‘Woman’s Right to Know.’48 Kenney goes on to assess this political ‘re-purposing’ of informed consent practices:

To be informed [in the context of these provisions] means having received the information required by the bill, but does not include […] the professional opinion of a doctor. […] Nor does it include any element of the social reality of the woman or the context informing her choice to end the pregnancy. (ibid.)

Although Kenney does not explicitly outline the ways in which the application of these provisions may be differentially and disproportionally enforced in the context of anti-black racism and misogynoir, there is a clear and useful claim that these regulations are ‘consistent with long-standing abortion myths […] that [endanger] women’s health’ (167).49 As Kenney states it:

The medical risks of abortion as well as of pregnancy and birth remained the formal domain of medical expertise until the recent incursion of state regulations into this arena.

[…] Abortion policy has long been at the confluence of medicine and politics, and analysis of abortion policymaking can illuminate the ways these two dimensions of gendered social control overlap. (2020, 157)

Historically, the conditions pre-pregnancy carried over those white interests with white privileging when it came to narratives around the use and distribution of birth control. Harriet Washington describes the protests by black communities against birth control because its original employment was intended to be genocidal. In fact, as Washington describes it, ‘These genocidal fears were dismissed as paranoia, but prominent white physicians had long advocated a reduction in black births as a means of pinching off the race’ (2006, 198).

As valuable as this challenge to birth privilege as white privilege may be, we still have issues of narratives around the experience of postpartum care as well as the uncritical narratives and norms of heteronormativity as they too dominate the conditions and context of even the birth equity and justice movements, not covered here.50

If the conditions by which one gives birth are operating as both epistemic violence and injustice underwritten by white privilege, protected publicly and in policy by white ignorance, and if the pre-conditions of pregnancy are already racialized, misogynist, coercive and trauma inducing, then, as Andrews has similarly testified in our conversation, to paraphrase, ‘there is a [demonstrated] hatred of women generally, but there is a real hatred of black women.’ If the issue is medicalisation (or perhaps, overmedicalisation) of pregnancy, one reparative effort is to reorganise and humanise the birthing environment.51 If one has only the outcome of childbirth premised on a fundamental right to have a child, to be cared for and tended to in the experience of pregnancy, then there needs be an investment in this right against all white entitlements to birth. We ought to engage a privileging of the subtle forms of knowledge derived from these experiences while divesting in those frameworks and infrastructures that favour white entitlements.

As a final thought, one outcome to this inquiry and a response to these violent injustices and disproportionality of harm described here might begin with how we could better gift time – time to labour, time to rest, time to process, time to build bonds, to deescalate fears, and to recover. In this same way, we must recognize the urgency of birth equity, because, in the words of doula care provider, Nubia Martin, it is still ‘an SOS situation’ (Aftershock, 52m32s).

Notes

- In my work, I argue that this ‘plot of entanglement’ is that all value of pregnancy centres on the production of a (healthy, non-disabled) baby such that ‘miscarriage is hauntingly unthinkable’ (2017, 211). This sets up (and is a ‘set up’) so that a pregnancy is successful when it conforms to this production and a ‘failure’ when it ends without a child in the end. This paper extends to this analysis by adding how this plot is also about the production of whiteness and white entitlements. [^]

- See Andrews’ work here on The Clearbirth Podcast, “Postpartum work and the doula calling featuring Valencia Andrews,” (Episode 3, 2020): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hL6KsrbDUfQ and a profile of her doula services here: https://www.ashebirthingservices.com/valencia. [^]

- A draft version of this paper was given as a presentation for the History of the Philosophy of Pregnancy Conference as part of the Richard R. Baker Colloquium Series, University of Dayton, Dayton, OH., October 2023. Thank you to the organizers and attendees who gave wonderful support. Thank you also goes to Katja Čičigoj, Lisa Johnson, and Youn-Joo Park for their careful editorial support for this paper. Of course, I am indebted to Valencia Andrews for our conversations and her contributions to this paper. The research utilized in this part was partially subsidized by a Molloy University faculty research grant. [^]

- See Scuro, ‘The Childbearing Teleology,’ (2017, 189–195). [^]

- Andrews notes that in her experience of doula care, there can be a use of Child Protective Services as a threat over women: ‘If you don’t do what we suggest (which is a show of dominance disguised as a suggestion), then [x] will happen to your baby.’ The fill-in of this blank includes a real threat of kidnapping, death, etc. To which she adds: ‘specifically using this term as a description of removing babies from parents with no real grounds for such a move.’ [^]

- An example of this parallel be found in, ‘The pervasive issue of racism and its impact on infertility patients: what can we do as reproductive endocrinologists?’ by Yetunde Ibrahim and Temeka Zore in The Journal of Assistive Reproduction and Genetics (2020 Jul; 37(7): 1563–1565):

[^]There is well documented poorer access to obstetric care and poorer obstetric outcomes in black women compared with their white counterparts; this issue is likely multifactorial, but we cannot ignore that blacks are more likely to be socially disadvantaged. Increased prevalence of preterm birth, maternal mortality, foetal growth restriction, and foetal demise, just to name a few, have contributed to the overall burden of disease disproportionately affecting black women. […]

Moving towards our own field of infertility care, there have been several studies over the past two decades that have documented the African American plight in regard to fertility treatment. We know infertility impacts around 12% of women, but black women may be twice as likely to experience infertility compared with white women; however, they are 50% less likely to seek out care … In the words of Reverend Stacey Edwards-Dunn who created Fertility for Coloured Girls, a national organization for African American women going through infertility after her own experience with infertility, ‘Infertility is a taboo topic of discussion in our community […] I was living in shame […] It’s expected that we are hyperfertile, that we’re baby-making machines…so we live in shame,’ (¶¶5–6)

- One of the surprising discoveries in conversation with Andrews is how the fear of not surviving one’s pregnancy motivated many of the last-minute decisions of her clients to submit to the perceived authority and the implicit agenda of the medical staff to ‘move things along.’ She remarked on how birth plans would get changed during labour, not out of self- determination but, she suggested, from the perceived pressure and fear driven by the statistical threat of the black maternal mortality rate. She also commented that it is “not just the statistics,” and that ‘the very reason the stats are what they are – racism.’ She observed many times how, problematically, there is both an ‘ultimate trust in and/or fear of the authoritative figure … [as] the representative of the white supremacist system.’ (Recorded conversation with V. Andrews, 10/1/2023. All references to my conversation with Andrews from this point on are from this personal communication.) [^]

- From City of New York, (2024): ‘Although maternal mortality in NYC has declined since 2001, the Health Department recorded 57 pregnancy-associated deaths in 2019. The maternal mortality crisis is especially severe for Black New Yorkers. The pregnancy-related mortality ratio for Black women in NYC is more than nine times that for White women.’ More recently, there has been corrections on the reporting of maternal mortality rates nationwide in the U.S., with the rate still high compared to other developed nations and with the racial disparities still quite large. See NPR.org’s reporting from May 2, 2024 (https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/05/02/1248563521/maternal-mortality-rates-2022-cdc):

[^]There continue to be enormous racial disparities in the U.S. maternal mortality rate as well – the rate for Black women was 49.5 deaths per 100,000 births in 2022, compared to a rate of 19 deaths for white women. Research shows the vast majority of these deaths are preventable. (¶5)

- This is cited by the grieving partner of one of the women in the documentary Aftershock, (Eiselt & Lee, dirs., 2022, 26m15s). [^]

- In ‘Doulas, Racism, and Whiteness: How Birth Support Workers Process Advocacy towards Women of Colour,’ Salinas et al. (2022, 3) discuss the importance of doula care for the birth experience, especially in the context of ‘obstetric racism’:

They are citing Davis (2019), ‘Obstetric racism: The racial politics of pregnancy, labor, and birthing’ (Medical Anthropology, 38, 560–573). [^]These harmful conditions show that the treatment of Black women and other women of colour is shaped through obstetric racism, creating specific conditions of racial inequality that must be significantly addressed by the medical community as well as by birth support workers. Davis (2019) finds that doulas can mitigate the conditions of obstetric racism through their support of Black women in these settings.

Fortunately, doulas already receive in-depth training to support birthing persons and take a holistic approach to center the non-medical physical, social, and emotional needs of their clients. They are acutely aware of the factors of obstetric violence and how to mitigate unnecessary interventions as well as helping their clients achieve the birth they are seeking.

- I discuss the Dobbs decision here for The Blog of the APA (July 25, 2022): ‘What Should Philosophers Do in Response to Dobbs? A Conversation With Ethicists.’ https://blog.apaonline.org/2022/07/25/what-should-philosophers-do-in-response-to-dobbs-a-conversation-with-ethicists/. [^]

- While Roe v. Wade provided a protection for reproductive rights at the federal level through the judiciary, the Dobbs decision by the US Supreme Court moves the regulation and restriction of reproductive care (including access to birth control and abortion) to the states, preconditioning the possibility of federal mandate either by a federal law or executive order at a later time. For more on this, see Human Rights Watch’s account here: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/04/18/human-rights-crisis-abortion-united-states-after-dobbs (April 2023). [^]

- From an opinion piece for the ACLU (The American Civil Liberties Union), ‘The Racist History of Abortion and Midwifery Bans: Today’s attacks on abortion access have a long history rooted in white supremacy’ (7/1/2020). https://www.aclu.org/news/racial-justice/the-racist-history-of-abortion-and-midwifery-bans. [^]

- From my conversation with Andrews, some additional examples of her doula care practices:

She adds that she conscientiously incorporates ‘ancestral healing practices related to pregnancy and postpartum care i.e., herbal baths, binding post birth, herbal skincare relief, womb care and naming and honoring the time as a period for resting, to be celebrated – to be steeped in love, possibilities and empowerment.’ [^][…] encouraging clients to practice self-advocacy in all spaces, I offer a greater and broader focus on self-care during prenatal and postpartum visits, as well as during labor and delivery; reconnecting clients with community who share similar values and experiences and can offer help and safe spaces for recovery and thriving in postpartum, setting up meal-trains for the new family, exploring different forms of body movement during pregnancy, encouraging clients to delegate their needs and accept support, exploring varying methods of feeding, guiding clients through changing their narrative around pregnancy and birth, despite and in spite of the statistics and traumatic birth stories pooling in our (BIPOC) communities, working with clients’ families and partners to show how they can be more effective at caring for the birth client in ways that allow them to focus on their maternal experiences and also feel supported in their caregiving roles.

- Citing Dotson as length here (2011, 239):

[^]Assessments of which kinds of harm result from epistemic violence are […] context-dependent exercises. Insofar as the harms of epistemic violence are hardly ever confined to epistemic matters, the harm resulting from pernicious ignorance that interferes with linguistic exchanges will require a case-by-case analysis. That is to say, ignorance that is perfectly benign in one epistemic agent, given a certain social location and power level, would be pernicious in another epistemic agent. A manifestation of ignorance that is reliable, but not necessarily harmful in one situation, could be reliable and harmful in another situation. Pernicious ignorance should not be determined solely according to types of ignorance possessed or even one’s culpability in possessing that ignorance, but rather in the ways that ignorance causes or contributes to a harmful practice, in this case, a harmful practice of silencing. Epistemic violence, then, is enacted in a failed linguistic exchange where a speaker fails to communicatively reciprocate owing to pernicious ignorance.

- Here I am previewing my application of Cherry’s Lordean rage, see nt. 29. [^]

- Andrews commented in our conversation on the ideas of white scepticism and white ignorance embedded in this illusory neutrality of research and data collection: ‘I believe this is partially fuelled by methods of collecting substantial data. I am often asked, by young NYC graduate students researching maternal mortality rates, how to quantify racism experienced in the birth room and beyond.’ [^]

- My first pregnancy would also be a miscarriage of a ‘blighted ovum.’ This experience removed much of the naiveté that I had presumed. [^]

- As I have argued it here, responding to Goswami’s claims in Subjects That Matter (2019): ‘The Postcolonial and the Post Traumatic: Specters and Syndromes of White Feminist Canon’ in philoSOPHIA: A Journal of transContinental Feminism, Issue: ‘Going Polyphonic I: With Namita Goswami et al.,’ (edited by Alyson Cole and Kyoo Lee, Volume 13, 2023, pp. 25–40). https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/52054. [^]

- Shah attributes the rising trend in maternal mortality, with the higher risk for black women, to increased frequency of c-section surgeries. He states that while he ‘believes that c-sections are life-saving surgeries,’ complications are three times more likely than with a natural delivery, and ‘Black women have a higher rate of c-sections.’ [^]

- This is a phrase taken from Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection (2022, 76). [^]

- This is Kristie Doston’s term, summarized here by Heidi Grasswick (2017):

[^]Doston (2011) characterizes such failures to recognize someone as a knower as an epistemic violence perpetuated on the speaker – a particular kind of silencing that she refers to as testimonial quieting. […] Dotson points out that epistemic violence and a coerced silencing of speakers restrict their testimony to hearers because they know their testimony will not be understood and given proper uptake by perniciously ignorant hearers’ (author’s emphasis, 260–61).

- DeGruy’s concerns and use of this kind of intergenerational transfer of trauma are more psychoanalytic and behavioural, which is not an approach or context I seek to utilize here. There may be elements of ‘victim blaming’ that I am actively avoiding in my ‘threading’ of the trauma history of slavery to current issues of maternal mortality rates and the epistemic injustices surrounding birth. [^]

- Fast-forward and counter this with the narrative given to what Anna Gotlib describes the ‘motherhood mandate’ of dominant ‘pronatalist’ discourses, of which she rallies against the ways that choosing childlessness invalidates women’s self-perception and social standing, and instead, defends how it ought to be validating: ‘By “pronatalism,” I mean an attitudinal stance that favours and encourages childbearing, as well as supports policies and practices that construe and venerate motherhood as the sine qua non of womanhood’ (2016, 331). Gotlib also links this pronatalist cultural trope to conservative political agendas that restrict access to reproductive care or mandate forced ultrasounds (335–336) and how this also manifests in the medicalisation and stigma around infertility (337). Gotlib goes on to describe how ‘voluntary childlessness’ is a kind of deviance but does not specifically address how this discourse may be infused with white privilege. Gotlib does note, ‘pronatalism perpetuates racist, heteronormative, and classist narratives about motherhood, […] premised on the relative “desirability” of motherhood’ (344). [^]

- For more on this, see Khiara Bridges’ discussion of DuBois’ double-consciousness in relation to American-ness and whiteness (2011, 219–220). [^]

- See Talia Lewis’ definition of ‘anti-black ableism’ as ‘redundant and contradictory simultaneously […] because ableism and anti-Blackness are mutually inclusive and mutually dependent.’ https://www.talilalewis.com/blog/why-i-dont-use-anti-black-ableism. [^]

- There is some evidence that it is predominantly white, heterosexual women who seek infertility treatment as well. See ‘Racial disparities in fertility care have persisted for years. Here’s why,’ NBC News (Nov. 17, 2022). https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/racial-disparities-fertility-care-persisted-years-s-rcna57690. There an interesting case study on the way whiteness becomes a protection of ‘property,’ as outlined by Desiree Valentine, see ‘The Curious Case of Cramblett v. Midwest Sperm Bank: Centering a Political Ontology of Race and Disability for Liberatory Thought,’ (Journal of Speculative Philosophy, [2020], Vol. 34[3], pp. 424–440). [^]

- Harris outlines two forms of whiteness as property: status property and modern property. She analyses this in the context of U.S. legal decisions like Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education. One significant application in her analysis is to affirmative action legislation. This could similarly be applied to the new decisions emerging from the U.S. Supreme Court regarding reproductive rights and care access, as with the recent Dobbs decision. The expansion beyond the legal definitions of ‘whiteness as property’ have larger historical, cultural, and psychosocial impact that continue to frame ideas neutrally and uncritically about reproduction out of this white privilege that emerged from ‘de jure and de facto segregation’ (1993, 1777). From Harris:

[^]The assumption that whiteness is a property interest entitled to protection is an idea born of systematic white supremacy and nurtured over the years, not only by the law of slavery and “Jim Crow,” but also by the more recent decisions and rationales of the Supreme Court concerning affirmative action. (1766)

[…] The legal affirmation of whiteness and white privilege allowed expectations that originated in injustice to be naturalized and legitimated. The relative economic, political, and social advantages dispensed to whites under systematic white supremacy in the United States were reinforced through patterns of oppression of Blacks and Native Americans. Materially, these advantages became institutionalized privileges, and ideologically, they became part of the settled expectations of whites – a product of the unalterable original bargain. The law masks what is chosen as natural; it obscures the consequences of social selection as inevitable. The result is that the distortions in social relations are immunized from truly effective intervention because the existing inequities are obscured and rendered nearly invisible. The existing state of affairs is considered neutral. (1777)

- This idea of ‘enragement’ is my way of aligning the outrage/outrageousness of the situation of maternal mortality rates and the systemic misogynoir with Cherry’s application of Lordean rage (2021), as impetus for my threading these elements of trauma history to current sabotages and subjections as it is also connected to the history of slavery. It seems to me that Lordean rage best describes the moral response for how disproportionately racialized one’s experience of pregnancy and one’s capacity to be self-directed in the generation of a birth narrative seems to be. [^]

- Hartman also describes the style of analysis in Scenes of Subjection as a ‘work of reconstruction and fabulation,’ in which, she explains that:

[^]My reading of slave testimony is not an attempt to recover the voice of the enslaved but an attempt to consider specific practices in a public performance […] but also […] the censored context of self-expression […] and the tactics of withholding aimed at not offending white interviewers and/or evading self-disclosure’ (15).

- We can transpose this as a similar subtext at the event of birth as I have described it previously, see ‘Griefwork: How Do You Get Over What You Cannot Get Over?’ (2017, 223–244). In the context of miscarriage, the pain of pregnancy loss is not really ‘pain’ of a death in the same kind of recognized way. In the context of post-partum, especially if there is a baby ‘to be had,’ grief in birth is ‘consolable’ and not a ‘memorable’ kind of pain. This is the assumption, operating like a testimonial smothering, that, ‘as long as you give birth to a healthy baby, you forget all the pain of childbirth.’ When there is a baby born, the motherhood narrative only affectively transfers that she should be ‘be happy.’ Still, the grief of surviving pregnancy that does not produce a baby is unthinkable and without narrative. These forms of grief and pain in miscarriage and post-partum could be re-read as another racialised form of testimonial smothering and violence. See also Scuro, ‘Thoughts on the Post-Partum Situation’ (Frontiers in Sociology, Vol. 3 [2018]: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2018.00013). [^]

- Paraphrased from Aftershock, (41m11s & 39m55s). [^]

- This is in reference to forms of epistemic injustice as described by Kristie Dotson previously noted. [^]

- I want to note here the importance of a concept in Critical Disability Theory, ‘access intimacy,’ as it may be applied to the call for care and interventions described in this paper. See Mia Mingus on the concept of access intimacy, ‘Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice’ (April 12, 2017): https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-and-disability-justice/. [^]

- Quoted at 38s & 2m34s in the film. These are in the voice-over narration and I think the first line is stated by Tina Braima and the second line is stated by Omisade Burney Scott, both of whom are featured in the film. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWbOgD5rQp0. [^]

- As discussed by care provider Helena Grant in Aftershock, (31m35s). [^]

- This is discussed by Dr. Yanica Faustin, Assistant Professor of Public Health Studies, Elon University, in Reclaiming Power, (9m52s). What happened to Serena Williams was also mentioned by an expectant mother in Aftershock (38m45s). [^]

- As noted in Reclaiming Power, ‘women are less likely to use pain medication or have a cesarean when a doula is present’ (12m47s–12m50s). In Aftershock, a nurse also narrates how being white and having access to white doctors ‘on call for you’ is a system failure (40m14s). [^]

- As paraphrased from Aftershock. Another example of this tension is illustrated in ‘Communal Pushing: Childbirth and Intersubjectivity’ (2014). Sarah LaChance Adams and Paul Burcher apply Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology to describe the intersubjective quality of pushing during labour, advocating for the ‘documented better labour outcomes.’ The communal push is a redistributed labour that is ‘support without a complete loss of bodily identity’ (77, 76). More pointedly, ‘This communication with others is fundamental to understanding the world as possessing a truth. […] Our gestures establish a common meaning’ (73). [^]

- One example of these forms of white proprietorship, is from Harriet Washington in Medical Apartheid (2006, 278) Washington explains the way in which the ‘Office for Protection from Research Risks (OPRR)’ led the way in exonerating those research institutions that studied ‘aggressive behavior in children’ under the cover story that it was to ‘prevent school shootings.’ Despite these mostly having ‘been carried out by white boys,’ the research was conducted on children of colour. The research regarded the use of fenfluramine as recently as the early 2000s. Washington assesses this:

Citing lawyer, Cliff Zucker, ‘OPRR’s decision has a discriminatory impact on children of color.’ [^]Despite the violation of confidentiality, the undue inducement, the medically risky nontherapeutic research, on healthy children that clearly violated federal guidelines, [… this exoneration] sent a clear message that no penalties would be ascribed to dangerous research if it were conducted on black children […]

- I found it difficult that the doctor who led the advocacy group, ‘TEAM Birth’ was focused on awareness in training doctors in racialised disparities and disproportionate risks in gynaecological care. He encouraged them to continue ‘Doing what we know but also having the patients see it.’ I think it is fair to read this suspiciously as he suggests that there be a consideration of the optics rather than offer a prioritisation of the injustices of the inequities and disproportionate risks. There is more evidence for my suspicion when, in the film, he is talking about the intentions of the TEAM Birth program with his ‘community partners.’ They discuss the training and program in the context of justice while he consistently mentions equity as his goal. One community leader, LaBrisa Williams, responds quite clearly, ‘you can’t have equity if you still haven’t made up for the other stuff that has been unequal.’ Dr. Shah did not hear the correction (47m10s–45s). [^]

- From Cherry’s The Case for Rage: ‘Taking its name from Audre Lorde, the Black feminist poet and scholar who first articulated the version of rage I’ll be exploring, Lordean rage is targeted at racism’ (2021, 5). [^]

- There is a longer discussion in the film of this transition from Black women midwives to the bond created between white male OB/GYN doctors and white nurses in which midwifery becomes a ‘book knowledge’ and a certification added to a nursing degree in the 19th and 20th century. As far as the profession of midwifery, ‘white women took over’ corresponding with public health marketing campaigns in which Black midwives were portrayed as ‘dirty’ and ‘unskilled’ (Aftershock, 58m8s–61m35s). [^]

- As narrated in Aftershock, (57m40s). [^]

- One report describes how policy to support doula care can offer significant impact and improvement for the current inequities (Hill, Artiga, & Ranji, ¶21):

[^]A variety of efforts are underway to increase workforce diversity and expand access to doula and other services to improve maternal and infant health outcomes and reduce disparities. Studies have shown that a more diverse healthcare workforce and the use of doulas may improve birth outcomes. The percent of maternal health physicians and registered nurses that are Hispanic or Black is lower than their share of the female population of childbearing age. The Biden Administration’s Blueprint includes efforts by HRSA to develop a maternal care pipeline to provide scholarships to students from underrepresented communities in health professions and nursing schools to grow and diversify the maternal care workforce. The use of doula services is another approach to increase diversity and expand the maternal health workforce. Doulas are trained non-clinicians who assist a pregnant person before, during and/or after childbirth by providing physical assistance, labor coaching, emotional support, and postpartum care. Pregnant women who receive doula support have been found to have shorter labors and lower C-sections rates, fewer birth complications, are more likely to initiate breastfeeding, and their infants are less likely to have low birth weights.

- Edited for clarity from auto-transcription. Andrews, in our 2023 conversation, would later note that when it comes to the complexity as to why there is a devaluation of doula care in a hospital setting:

In her experience, this results in ‘greater fear, higher blood pressure readings, increased foetal stress due to maternal stress.’ [^]I also know it’s NOT just a matter of saying ‘No.’ Sometimes it actually comes with consequences like: increased use of language like: you don’t want a dead baby, do you? By staff or staff aggressively questioning the person giving birth about why they don’t want to ‘move things along’ in this manner, what they’re waiting for or mentioning how their placenta is failing, and even bringing in a more assertive/bully of a doctor to also push the topic.